Beginning and Ending Lectures

Ultimately we hope students remember, and are able to use, what we teach! Two easy ways to help achieve this goal are (1) to start lecture with a brief outline of the material to be covered and (2) end lecture with a summary of the key points or “takeaways” (tell them what you are going to tell them, tell them, and tell them what you told them!) .

At the beginning of lecture, frame the content of the day’s lecture. For example,

- Use a “big idea” concept

- Today’s lecture connects to xyz

- List specific topics to be covered - with several possible formats

- Approaches to be used (eg. proof of xyz, case study, examples)

- Application to specific problem/market/product (be specific)

- Significance or connections or summary

Outlines should be specific to the day’s lecture, not a generic outline that gets used over multiples weeks. Alternatively, include key points under the specific topic instead of the approach and application.

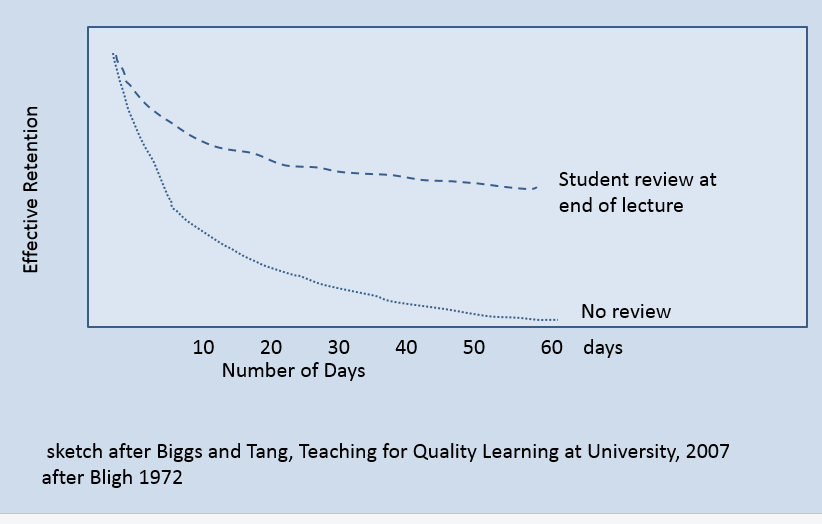

Similarly, students are more likely to remember material if they are reminded of the “important” points at the end of lecture (see figure 1 below). Reviews can be a simple summary slide or bullets written on the board. Note that you have to actually leave time for the summary for it to be of any value.

To avoid running late, one timing trick is to have an example about 3/4 of the way through lecture that can be expanded or compressed.

- On time - continue example as planned

- Running late - introduce example and approach but skip details

- Running early - (does this happen?) show them the level of detail you expect on an exam including written reasoning

Then you will arrive right on time for the review, a few minutes before each class ends.

Alternatively, you can ask students to spend the last few minutes of class writing down the main ideas, and then have them compare answers with a neighbor. This takes longer, but students will likely internalize the content more effectively.

1 Biggs, J., Tang, C. and Biggs, J. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill/Society for Research into Higher Education & Open UniversityPress. P. 109. [also available as a download from Cornell library.]